Last week, former Time Warner head Jerry Levin, marked the 10th anniversary of his disastrous merger deal with AOL by finally apologizing and accepting responsibility. Levin issued his mea culpa on CNBC explaining that he “presided over the worst deal of the century” and how sorry he is for “the pain and suffering and loss that was caused.”

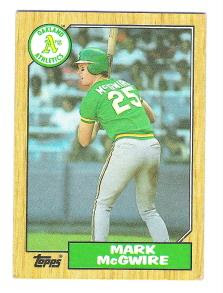

I thought of Levin’s apology the other day when I watched former baseball slugger Mark McGwire finally admit to taking performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) as a player. Sure, McGwire’s is a different admission of guilt. He’s more of a guilt-ridden cheat than Levin, who made a horrible business decision. No one lost their job because McGwire took steroids to bulk up and hit more homers. Yet, both of these apologies came many years after the actual deed was done.

I’m not going to get into the debate about whether there was anything actually wrong with players “juicing up” during the steroid era of professional baseball. If you’re interested in an insightful discussion on the topic, I recommend the recent book Cooperstown Confidential, by Zev Chafets. The author explains the results of the Mitchell Commission and takes baseball purist George Will to task for arguing that the steroid era altered the very essence of the game.

I’m not going to get into the debate about whether there was anything actually wrong with players “juicing up” during the steroid era of professional baseball. If you’re interested in an insightful discussion on the topic, I recommend the recent book Cooperstown Confidential, by Zev Chafets. The author explains the results of the Mitchell Commission and takes baseball purist George Will to task for arguing that the steroid era altered the very essence of the game.

The issue here is not only whether McGwire is truly contrite for using PEDs, but also whether he really feels remorse for his evasiveness and outright lying about his steroid use. While many of Mac’s fans (and Sammy Sosa’s) inevitably feel cheated knowing now that the famous homerun race of ’98 was between two ‘roid raging monsters, the real concern of baseball should be the unethical way McGwire handled the accusations over these many years.

The homer battle between Sosa and McGwire was actually a level playing field since both sluggers were juicing. Baseball purists will argue that McGwire’s numbers can’t be compared with the players of the past (e.g., Ruth, Maris, etc.) because of his unfair pharmaceutical advantage (Barry Bonds too for that matter). But these are debates to be had among stats fans and the history buffs of the game. The question of how the Hall of Fame will handle the stars of the steroid era is another thorny question, but not one that is germane to McGwire’s admission this week.

The question I ask as a rabbi is whether Mac’s confession should count as legitimate repentance (teshuvah). We’ve heard just about every form of “I’m sorry” from our sports stars throughout history (the philandering golfers, the wife-beating hoop stars, the drug-abusing baseball players, the gun-toting football players, the gambling refs, and on and on). But what exactly did McGwire apologize for? After all, he seemed to have plenty of excuses for his steroid use and even blamed the “steroid era” for what he did. He claimed he did it for his “health,” and not to be a better player. When asked if he could have hit all those dingers had he not juiced, without hesitation he said, “Absolutely. Look at my track record as far as hitting home runs. They still talk about home runs I hit in high school. I was given the gift to hit home runs.”

Doing real teshuvah and being contrite are not the same as regret or a confession. Whether he considers his juicing to be cheating or not, Mark McGwire still hasn’t owned up to his lying about what he did. It took him many years to finally admit that he used PEDs, but baseball fans everywhere are still waiting to hear him articulate that he understands how his evasiveness cheated the public. He must take responsibility for his actions.

McGwire returns to baseball this spring as the hitting coach for the St. Louis Cardinals. There are, of course, many who believe this is the only reason he finally admitted his steroid use. I’m willing to give him the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps, his admission now is because keeping those demons in the closet makes it difficult to live as a man. But in terms of performing teshuvah, Big Mac still has his work cut out for him. And no drug will make that task any easier.