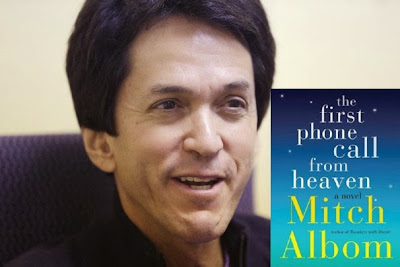

Albom sets “The First Phone Call from Heaven,” in Small Town America. The story takes place in Coldwater, Michigan where local townsfolk begin receiving phone calls from deceased relatives they recently lost. All around the same time the police chief hears from his deceased son who was killed in Afghanistan, a woman gets calls on her cell phone from her dead sister, and another woman starts getting calls from her mother in heaven. Believers – and protesters – descend on the small Northern Michigan town as word of the heavenly phone calls spreads by way of an up-and-coming television news reporter. Interwoven in this very spiritual story that centers on how we connect to heaven is the story of Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone. Just as people doubted Bell’s magical telephone would really connect people who couldn’t see each other, Albom seems to remind the reader that we shouldn’t be so skeptical about these calls from heaven.

Category: Theology

In Heschel’s memory I share my favorite story of Heschel as retold to me recently by Rabbi Gordon Tucker, one of his students: Heschel was sent by the Seminary to a Conservative synagogue to give a speech at a fundraising event. He went on and on for over an hour about his theology of humanity’s desire to conquer both Space and Time. It was highly intellectual and far over the heads of many in the audience who quickly lost focus. When Heschel was finally finished with his teaching, the president of the congregation got up and simply said: “You heard the rabbi, the Seminary needs more Space and there isn’t much Time!”

While Heschel died before I was born, his writings have had a significant impact on my own Jewish theology. In college I read Heschel’s The Sabbath which I have re-read several times since. My library has a dedicated shelf of Heschel’s works, many of which were inherited by me from my late Papa, David Gudes. My copies of Man in Search of God and The Prophets still have the dogeared pages that my Papa left.

In high school, as a member of USY’s AJ Heschel Society, I would stay up late at night learning about Heschel’s theology. I recall studying God in Search of Man with USY’s International Director Jules Gutin at International Convention in Los Angeles in 1993.

Over the years I have taught Heschel’s The Sabbath to adults and teens. The first time I taught that book to teens was as a college student at Camp CRUSY. It was after Shabbat dinner on a Friday night and somehow all twenty or so teens gave me their full attention. That was one of the pivotal moments in my decision to become a rabbi.

I also remember the first time I taught about Heschel’s theology of Shabbat to adults. It was during a Tikkun Leil Shavuot at Congregation B’nai Israel. Sitting next to the synagogue’s rabbi, Leonardo Bitran, I discussed how I fully embrace all the technological advances we have at the end of the 20th century and how my love of technology, electronics and automation often comes into conflict with Heschel’s Shabbat theology, which calls for a break from technological automation that makes our lives easier. Heschel believed that we humans use space to try and control time. I asked “Is Heschel’s notion of Shabbat a possibility? Can we, as humans in the 21st century, ever just allow ourselves to sanctify time without trying to conquer space and time in a tech-centered world?”

As society becomes even more dependent on technology in the 21st century, Heschel’s theology seems to gain importance. Heschel’s legacy is two-fold. He was a Jewish pioneer in the call for civil rights in our country and he pushed us to think intelligently about God’s role in our lives. Heschel’s ability to write poetically, if cryptically, about modern man’s challenge of letting time dictate our lives if only for a day has been a gift for generations and will be a gift for generations to come. May the righteous memory of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel continue to be for blessings.

In my final years of rabbinical school at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, I was living and working in Caldwell, New Jersey as a rabbinic intern. One of the congregants at the synagogue, Agudath Israel, was a professor at the College of St. Elizabeth in Morristown, New Jersey. She asked me to give a presentation about Judaism to the women in her undergraduate class. In preparation for my visit she asked the students to submit a list of five questions each that they would like me to consider. Without any exaggeration, a full 90% of the students included at least one question about Jesus Christ in their list.

I had received questions from Christians in the past concerning the Jewish view of Jesus, but that experience confirmed for me just how curious Christians are about how Jews understand Jesus in both historical and theological perspectives. Many of the women in that class at the College of St. Elizabeth were surprised to learn that Jews do not consider Jesus to be the messiah and the entire class was shocked to discover that Jesus’ teachings were not part of the required coursework I was doing in my rabbinical school studies. By far, to this day the most frequent questions I receive from Christians all have to do with the Jewish understanding of Jesus.

The topic of the contemporary view of Jesus among Jews has long been stuck somewhere between taboo and “we just don’t talk about it”. But now, thanks to two new books it is front and center. Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, who refers to himself as “America’s Rabbi” has written a new controversial book that will be released next week. For those who thought Boteach’s Kosher Sex was too radical, his new Kosher Jesus is sure to ruffle feathers. With Boteach, it is difficult to know if he writes these provocative books and articles because he’s genuinely passionate about the scholarly discussion it will generate or if he just lusts after the spotlight. Still playing up his friendship with the late Michael Jackson and very passively campaigning to be the next Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth, Rabbi Shmuley Boteach has been busy publicly questioning what all this fuss is about with his new book. In truth, Boteach knows that every Orthodox rabbi and scholar — from Chabad Lubavitch to the Haredim — who attack Kosher Jesus as blasphemous and its author as a heretic are only helping his book sales.

Boteach loves the attention he’s getting and in the weeks leading up to its release has been penning article after article fighting back against his naysayers. In a recent Jerusalem Post article, Boteach wrote, “Unless you’ve been a space-tourist with Virgin Galactic the past few weeks you will know that on [sic] February my new book will be published.” (There’s no doubt in my mind he received a generous kickback from Virgin’s Richard Branson for mentioning Galactic.) Media attention aside, I think Boteach’s book is important and will finally make it “kosher” for Jews to learn about and discuss Jesus as the historical figure.

Boteach’s book portrays the actual story of Jesus’ Jewish life as told in both early Christian and Jewish sources. If you ask most Jews to tell you about the historical figure of Jesus, their response often turns fuzzy after a quick introduction that he was Jewish. Kosher Jesus explains how Jesus was a Torah-observant teacher who instructed his followers to observe the Torah. Jesus’ teachings were quoted extensively from the Torah. And before being murdered by Pontius Pilate, Jesus fought Roman paganism and persecution of the Jewish people. His death was retribution for his rebellion against Rome.

No matter what one believes Boteach’s intentions were in writing this book (more fame, more money, a Chief Rabbi position, setting the academic record straight, or a combination thereof), he clearly did his research on the subject and has taken away the taboo of Jews discussing Jesus of Nazareth. Hopefully, Boteach’s book will give Jews the ability to go a little deeper in their understanding of Jesus. This will be helpful for rabbis like me who often field questions about Jesus from Christians, but it will also prove useful for Jews living in predominantly Christian areas as well as for the Jewish college student with a Christian roommate or agressive missionaries on campus.

|

| Rembrandt’s portrayal of Jesus is more apparently Jewish than other artistic renderings |

As I have been reading the many criticisms of Rabbi Shmuley Boteach and his Kosher Jesus, one thing that I’ve noticed is the strong discomfort his attackers have with even mentioning Jesus. As Josh Fleet mentioned in his Huffington Post article, some of Boteach’s critics refuse to even type out the name Jesus. Instead they refer to Boteach’s book as Kosher J. abbreviating the name of Jesus in a way that is reminiscent of how they refuse to spell out the word “God” or “Lord” choosing instead to use “G-d” or “L-rd”. This struck me as odd as it seems to put Jesus in the same category as God whose name must not be rendered in print (even though the English words “God” and “Lord” are not actual names for the Jewish deity and I’ve never understood a ban on spelling out God’s name in Latin characters). In any event, it is similarly odd that many of Boteach’s critics who are eager to put him in herem (excommunication) for having the chutzpah to publish a book about Jesus of Nazareth are the same Chabad Lubavitch members who seem to be placing their bets that the late Lubavitch rebbe is the messiah. One man’s false messiah is another man’s god. One man’s spiritual leader is another man’s messiah.

I especially like the way Josh Fleet concludes his article about the sharp criticism of Kosher Jesus. Fleet writes, “In 2012, the topic of Jesus should not be a Jewish taboo. If we believe so much that our relationship with Christianity is based on deceit, tragedy and senseless hatred — that it has broken us — then we are obligated to believe it can be based on trust, opportunity and boundless love — that it can be fixed.” Well stated, and I believe that what will equally help fix the way Jews deal with the topic of the historical Jesus will be the new contribution by Brandeis Professor Marc. Z. Brettler and Vanderbilt Prof. Amy-Jill Levine. Their new version of the New Testament is revolutionary in that it has been published for Jews.

I am always surprised when Christians are surprised that New Testament studies was not part of my academic courses in rabbinical school. No matter how many times I explain that Jews do not believe our Torah has been superseded by the “New Testament”, Christians still don’t understand this concept. It’s as if they think that we’re big fans of the first Godfather movie and yet refuse to watch the sequel. In truth, most Jews who are knowledgeable about the Jewish Bible have little clue about the narrative of the “New Testament”. One of the primary reasons for this has been the Jewish ban on studying Christian religious texts for theologically dogmatic reasons. However, the new version that Brettler and Levine have put forth seems to make this scholarship safe for Jewish students.

An article in the USA Today explains Prof. Levine’s intentions in completing this project:

The project, published in November by Oxford University Press, is the latest effort in Levine’s lifelong quest to help Jews and Christians understand each other better.

That quest started when she was growing up among Portuguese Roman Catholics in North Dartmouth, Mass. She was fascinated by her schoolmates’ faith and horrified when one of them told her that the Jews had killed God by crucifying Jesus.

She made it her life’s work to prevent Christians from spreading that kind of anti-Semitic claim and to help build a bridge between the two faiths.

After all, she said, Jesus and his early followers were Jews. So the two faiths have much in common.

The Annotated New Testament points out places where Christians get Judaism wrong.

“The volume flags common anti-Jewish stereotypes, shows why they are wrong and provides readings so that the Gospel is not heard as a message of hate,” Levine wrote in an email. “These stereotypes include the Old Testament/Jewish God of wrath vs. the New Testament God of love and the view that Judaism epitomized misogyny and xenophobia.”

When you consider how little most Jews know about Jesus from a historical perspective, it is actually an exciting time when this discussion will no longer be taboo. While some religious Jews will claim it is dangerous to read books like Kosher Jesus or to have Brettler and Levine’s commentary of the “New Testament” on your bookshelf for reference, I actually think that this will lead to better Jewish-Christian dialogue. It will also alleviate so much of the misinformation and ignorance that many Jews have about Christianity and its roots. I’m eager to see where this leads and I’m grateful to Rabbi Shmuley Boteach for having the conviction to publish Kosher Jesus, and to Profs. Brettler and Levine for using their scholarship to educate us on a religion about which we have been hesitant to learn more.

I published my first blog post on the Huffington Post website back in October. What immediately amazed me was the large number of comments posted about my piece. In the first couple of days there were close to 500 responses to what I had written. And then I began to skim these “talkbacks” to find that the vast majority were written by individuals who were angry about any form of organized religion and believed that God was as make-believe as Mickey Mouse. I was surprised to see so many self-affirmed atheists not only lurking on the religion section of the Huffington Post, but also being its most vocal contributors. It should be noted that my blog post had little to do with God and was devoted to post-denominationalism in Judaism. Most of the comments were from lapsed Christians who now felt religion was a joke and seemed angry that it was still in existence (in any form).

I planned to write about this phenomenon, but never got around to it. So, I was glad when my colleague Rabbi David Wolpe, of Los Angeles, posted his feelings about it on the Huffington Post yesterday (“Why Are Atheists So Angry?”). In a much more eloquent way than I could, Rabbi Wolpe put into words his take on why there are so many atheists participating in the online conversation on websites devoted to religion — and why their comments are so tinged with angst. When I first read his post yesterday there were no comments, however, when I checked back today there are now close to 900 responses — certainly with a good number of them from the atheist community.

Rabbi Wolpe writes:

How harmless is it to post an article about why people should read the bible on a site devoted to religion? I did on this very page, and it evoked more than 2,000 responses, most of them angry. I had previously written a similarly gentle article about how God should be taught to children that evoked more than 1,000 responses, almost all negative and many downright nasty.

It is curious that a religion site draws responses mostly from atheists, and that the atheists are very unhappy. They are unhappy with the bible (“foolish fairy tales” is one of the more generous descriptions), unhappy with the idea of God (the “imaginary dictator” whose task in human history, apparently, is to ensure that oppression and evil triumph) and very unhappy with anyone (read: me) who presumes to offer religious advice to the religious. Only the untutored assume that religious people predominate on websites (Huffington Post Religion page, On Faith in the Washington Post, Beliefnet.com) devoted to religion.

In the past when I have debated noted atheists — Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and others — the audience was heavily weighted toward my opponents. That makes sense. Each of these men — like Dawkins, Dennett and others — brings with them a large following. But why seek out a religious site solely to insult religion?

To summarize, Rabbi Wolpe offers four four reasons why he believes atheists are so angry. First, Atheists genuinely resent the evil that religion has caused in the world. Second, they are convinced that religion is a fairy tale that impedes science/progress/rational thought. Third, “there is an arrogant unwillingness to engage with religion’s serious thinkers.” And, finally, he argues that “there is sometimes in the atheist a want of wonder. In a world in which so much is still not understood, in which multiple universes are possible, in which we have not pierced the mystery of consciousness, to discount the supernatural is to lack the openness to mystery that should be a human hallmark. There is so much we do not know. Religious people too should acknowledge this truth.”

Perhaps websites like the Huffington Post and Beliefnet should offer a section devoted solely to atheism so that the atheists would no longer dominate the airwaves in the religion section with with their angst. Or perhaps, these individuals will continue to weigh in on the discussions surrounding religion, but will do so in a more civil manner that will actually move the conversation forward in a productive way. I know deep down that these individuals are still seeking. They are still interested in the conversation and have their fleeting moments of belief; otherwise I don’t think they’d spend the time engaged in the debate.

Just because LeBron James started meeting with a rabbi this summer doesn’t mean he’s ready to be dispensing theological statements.

I’ve been thinking a lot about LeBron’s statement via his Twitter feed last week about the Cleveland Cavaliers’ huge upset to the Lakers. In what has become known as the “Karma Tweet,” LeBron tweeted the following during the final minutes of his former team’s 55-point loss to the Los Angeles Lakers: “Crazy. Karma is a b****.. Gets you every time. Its not good to wish bad on anybody. God sees everything.”

There are many unknowns when it comes to theology. Aside from dealing with the conundrums of evil and suffering in the world, we really don’t know whether God is omniscient. Apparently, LeBron James is certain of God’s omniscience (“God sees everything”). Not only that, but it seems that LeBron’s God metes out justice on those who “wish bad on anybody.” Now, I’m not going to judge LeBron for his theological certainty or even for his brashness in tweeting these words. I am, however, going to call him out for the senselessness of tweeting about divine karma this way.

That tweet couldn’t possibly have been received well no matter what happened. LeBron handled his separation from the Cavaliers in the worst way imaginable, so criticizing owner Dan Gilbert or the Cavaliers for wishing ill on him is ridiculous at best. Second, LeBron’s “Karma Tweet” sets him up for ridicule should the karma now fly the other way, which is exactly what has happened. Since LeBron decided to wax theological on Twitter, his team — the Miami Heat — has lost three consecutive games on the road and has seen the three superstars all get injured (twisted ankles for LeBron and Chris Bosh, and a hurt knee for Dwayne Wade).

This only proves that if you believe in the divine karma LeBron believes in, well, it can cut both ways. And if you ever sense that, thanks to karma, bad things are being levied on those who wished ill on you, be smart about it and keep your mouth shut. And in this day and age, that means stay away from Twitter!

One of my favorite movies as a kid was 1987′s “Stakeout” starring Richard Dreyfuss and Emilio Estevez. Watching the movie on VHS (remember those?) years later as a college student at around the same time I was discovering the writings of the Jewish theologian and civil rights activist Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, I don’t recall ever thinking to myself, “You know, that Richard Dreyfuss is so good at playing Detective Chris Lecce in “Stakeout,” he’d do a fine job playing Heschel too.”

But, Dreyfuss has actually gotten rave reviews playing Rabbi Heschel in “Imagining Heschel” at the Cherry Lane Theater in New York. This, of course, isn’t the first time the actor played a teacher. After all, he played music teacher Mr. Glenn Holland in the 1995 film “Mr. Holland’s Opus.”

I am a finalist in the January/February 2010 Moment Magazine caption contest. Please vote for me by clicking here.

This is the cartoon (by Bob Mankoff) and the caption I wrote:

“Is there a charge to download with that? Because I don’t think this people will go for it.”

“Here’s version 2.0, but please don’t throw this one, it’s not under warranty?”

I was surprised by how much I enjoyed James Cameron’s film “Avatar.” It is unusual for me to enjoy a fantasy movie so much that I have to see it a second time in the theater, but this was the case with this 3-D film about a futuristic planet (Pandora), inhabited by an indigenous population that is destroyed by a human army in its effort to mine a precious mineral called “unobtanium.”

Knowing that the local tribe on Pandora is called the Na’vi, the Hebrew word for prophet, I went into the theater listening closely for other Jewish references or connections. And I found several.

There have been some very interesting articles about the Jewish connections in Avatar. Never one to disappoint with his scholarly understanding of theology and theodicy, Jay Michaelson penned two separate articles about Cameron’s Avatar. In his Huffington Post essay, the author of “Everything is God” explains the theological underpinnings in the film. He writes, “Avatar’s Na’vi subscribe to a combination of pantheism and theism, a view scholars today call “panentheism.” As scholar of religion Gershom Scholem observed, panentheism is usually rooted less in faith, as the New York Times’s Ross Douthat said, than in experience. Like mystics here on Earth, the Na’vi have an experience of unity of consciousness with other beings, all of which (themselves included) are really just manifestations of one Being, which they call Ai’wa.”

In his article in The Forward, Michaelson focuses on the environmentalism theme of the film. He explains that the philosophy of Avatar “is a bit of pantheism, a bit of nature mysticism and a surprising dash of monotheism, as well. In other words, it’s Kabbalah, as filtered through the Hasidism of the 19th century and the neo-Hasidism of the 20th and 21st. “Avatar” tells the story of Pandora – the world of the Na’vi – threatened by human ore mining. Where “Avatar” departs from classical Kabbalah and Hasidism is in its environmentalism. Classical Kabbalah and Hasidism do not speak in “Avatar’s” environmental terms, because “environmentalism” would have made no sense to people living before the Industrial Revolution.

![]() Rabbi Benjamin Blech, on the Aish.com website, covers many of the obvious Jewish themes in Avatar (Na’vi, man versus God, shomrei adama/protectors of the earth, etc.), but adds some fresh ideas as well. I especially like his theory that the mountains that hung over the heads of the Na’vi population are reminiscent of the midrash explaining that God held Mt. Sinai over the heads of the Israelites like an inverted cask (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 88a).

Rabbi Benjamin Blech, on the Aish.com website, covers many of the obvious Jewish themes in Avatar (Na’vi, man versus God, shomrei adama/protectors of the earth, etc.), but adds some fresh ideas as well. I especially like his theory that the mountains that hung over the heads of the Na’vi population are reminiscent of the midrash explaining that God held Mt. Sinai over the heads of the Israelites like an inverted cask (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 88a).

Sergey Kadinsky, writing on Heshy Fried’s “Frum Satire” blog, connects the outsider’s experience of Avatar protagonist Jake Sully trying to fit into the Na’vi community with a convert to Judaism. He also notes the similarities between the Na’vi method of slaughter and that of the shochet (Jewish ritual slaughterer).

I found several other Jewish connections in Avatar; whether Cameron intended them or not, I don’t know. There are also a lot of connections to other religions including Christianity. In fact, I read an interview with James Cameron in which he said he wanted to have as many different faith traditions represented in the film as possible. Supposedly, the scene in which Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) carries the dead Dr. Grace Augustine (Sigourney Weaver) at the end of the film is supposed to be a reversal of Mary carrying Jesus. And I’m sure the name “Grace” is intentional.

Perhaps the main character’s name “Jake” is intended to be like “Jesus” or maybe even the biblical patriarch Jacob. Since Jake Sully is transformed, his character could indeed be a link to Jacob who has to endure a wrestling match with God’s angel (Genesis 32:4-36:43) before his name is changed and he becomes the leader of the people. Jake Sully had to wrestle the toruk to be transformed and accepted by the people. After wrestling the toruk, he is able to connect to the being in a very powerful way. Jacob’s connection with God was bolstered following his transformative wrestling experience. Additionally, Jake Sully had to go to a holy place (The Tree of Voices) before being accepted and it is in this holy place where he goes to sleep and dreams (When Jake sleeps as the Avatar, he wakes up as his human body). Jacob renamed the place in which he dreamed Beit El (House of God). Both Jake Sully and the Patriarch Jacob didn’t realize the places they were in were holy until they fell asleep there.

The “J” name for Avatar’s protagonist could also be symbolic of other nevi’im (prophets) in the Jewish Tradition, like Jeremiah, Joel, Job, etc. or even biblical kings like Josiah.

In Avatar, a Navi became close to another Na’vi by saying “I See You” or “Oel ngati kameie.” Each time I heard this, I focused on the word n’gati, which could come from the Hebrew nogeah, to touch or become attached. Variations on this word include the Hebrew term “nogeah badavar” (to be involved with) or n’giah (to touch someone).

Blech might be on to something when he reminds his reader that “the root word navi really means seer, someone with the capacity to see more than others. And that is exactly the point of the story.” That is, the Na’vi in Avatar couldn’t predict the future (or they would have seen the impending doom of the human army), but they did understand the power in seeing the “other.”

I’m not sure if the name Neytiri (played by Zoe Saldana) has any connection to the Hebrew word neturei, as in Neturei Karta (Guardians of the City), but she certainly saw herself as a guardian of Pandora. I know that James Cameron was advised by many linguists, so any of these connections are possible.

Kadinsky’s comparison of the attack on the Tree of Voices to the Romans breaching the walls of Jerusalem and the ultimate destruction of the holy Temple in 70 CE is apt. There might be some connections as well between Pandora and Eden, with the Tree of Knowledge considered to be off limits and then “attacked” for gain (knowledge of self in the Torah and unobtanium in Avatar). Lastly, I think there is a connection between the name of the Na’vi spirit Eywa and the Tetragrammaton name for God (YHWH).

Sure, it’s possible to just watch Avatar as another Hollywood blockbuster/Oscar nominee and enjoy the beautiful CGI scenery, a simple plot, and a politically charged clarion call to conserve our natural resources, respect indigenous peoples, and protect our environment against big corporations that can afford their own army. But, I think it’s more fun to look for the connections with different faith traditions. Some, like the Pope, will find the religious messages of Avatar problematic. Others, will find deep spiritual meaning in these metaphors.

I ultimately choose to pay homage to the brilliant work of James Cameron. Not only did he create an entertaining epic, he also gave us some challenging topics on which to meditate.

I was in Israel staffing a Birthright Israel trip in 2004 when I learned about the Indian Ocean Tsunami while watching CNN in my Jerusalem hotel room. The following year, I was staffing a University of Michigan Hillel mission to Ukraine when the tragic news about Hurricane Katrina came on the news in my Kiev hotel room. I was therefore surprised that I learned of the devastation of the Haiti earthquake the other day while sitting in my own home, in the United States.

These natural disasters raise many challenging theological questions for us. The mere fact that we refer to these events as “acts of God” forces us to consider why God (whichever God we believe in) acts likes this — or why God allows these catastrophes to occur. Following the theology ascribed to Rabbi Harold Kushner, I would phrase the theological conundrum as: “How do we humans understand and relate to a God who doesn’t participate in these natural acts of devastation?” Because if these were really acts of the God in which I believe, I simply wouldn’t want that to be my God!

In the aftermath of the Indian Ocean Tsunami, I found some comfort in a prayer that Rabbi Jonathan Sacks wrote. I hope I also brought some comfort to others by reciting that prayer during that difficult time. Rabbi Sacks, the chief rabbi of the British Commonwealth, has adapted that prayer for the recent earthquake in Haiti.

As an introduction to the prayer penned by Rabbi Sacks, my teacher Rabbi Brad Hirschfield of Clal writes the following on his Beliefnet blog: How does one pray in the wake of this week’s events in Haiti? Or does that really beg the question of how we pray on any given day in the face of equally painful, if less grand, tragedies? I am not sure, and frankly right now, am not sure that I care.

Prayer in Response to Natural Disaster

By Sir Jonathan Sacks, Chief Rabbi

Adon ha-olamim, Sovereign of the universe,

We join our prayers to the prayers of others throughout the world, for the victims of the earthquake which this week has brought destruction and disaster to many lives.

Almighty God, we pray You, send healing to the injured, comfort to the bereaved, and news to those who sit and wait. May You be with those who even now are engaged in the work of rescue. May You send Your strength to those who are striving to heal the injured, give shelter to the homeless, and bring food and water to those in need. May You bless the work of their hands, and may they merit to save lives.

Almighty God, we recognise how small we are, and how powerless in the face of nature when its full power is unleashed. Therefore, open our hearts in prayer and our hands in generosity, so that our words may bring comfort and our gifts bring aid. Be with us now and with all humanity as we strive to mend what has been injured and rebuild what has been destroyed.

Ken Yehi Ratzon, ve-nomar Amen.

May it be Your will, and let us say Amen.